What follows is derived from a talk I gave at the New York Society for Ethical Culture a decade ago. I am revisiting it because of the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade and my efforts to parse what I think about the sanctity of life in relation to a woman’s right to choose. I am also compelled to return to it by the deeply divided nation I live in and the relentless attacks of one side of that division on principles I hold to be sacred.

Prologue

Current theory in Physical Cosmology tells us that the Universe exploded into existence approximately 13.8 billion years ago from a single point. That it emerged out of a singularity suggests there was nothing adjacent to be savaged by the blast.

About 13.7 billion years ago the first stars and galaxies began to form. Stars are massive nuclear furnaces where matter is subjected to unimaginable extremes of pressure and heat. Scientists tell us that stars eventually burn out, many of them with cataclysmic explosions, and then turn cold (relatively speaking) or collapse into very dense matter, some reach densities sufficient to become black holes. At some point in the very distant future our sun will die, taking with it any life that still exists on Earth.

About 3.8 billion years ago the first primitive life forms appeared and the workings of the survival of the fittest were set in motion. It was a microbe eat microbe world back then.

800 million years ago the first primitive animals appear and bring the competition to be the next big thing to a new level.

About 200 million years ago mammals emerge, but since the dinosaurs won the big thing competition long before that, they remain a secondary trend for some 135 million years.

About 65 million years ago the dinosaurs become extinct, the apparent victims of a random catastrophic event. An asteroid or comet collided with the earth, indiscriminately killing all life near the impact and altering long term environmental conditions to such a degree that the dinosaurs fail to survive. Mammals begin their ascent to become the next planetary idol.

About 300 thousand years ago Homo sapiens arrives. Soon after, geologically speaking, these intelligent creatures begin to ponder the world around them and observe that it is a dog eat dog world and nobody gets out alive.

About 170,000 years ago, a supernova explodes in the large Magellanic Cloud, destroying who knows what in the immediate vicinity and sending a brilliant flash of radiation out to the far reaches of space.

On the 24th of August, 79AD, Mount Vesuvius erupts, burying the city of Pompeii and indiscriminately killing everyone, the good, the bad, the men, the women, the children.

On August 26th and 27th of 1883 an eruption of Krakatoa culminates in a series of massive explosions heard as far away as Perth in Austrailia. The official death toll recorded by Dutch authorities was 36,417. Tsunami waves were experienced by ships as far away as South Africa. So far reaching are the effects that researchers have proposed that the blood red sky depicted in Edvard Munch’s painting “The Scream” can be attributed to the lingering effects of the explosion. Munch is quoted as saying “suddenly the sky turned blood red … I stood there shaking with fear and felt an endless scream passing through nature.” The painting was made in 1893, a full ten years after the eruption.

In 1987, earth-based observers witness a super nova in the Large Magellanic Cloud, 170,000 years after it happens.

In October of 2003, a young boy was playing beneath the clay bluffs on Block Island, Rhode Island, and was suddenly buried under a dump truck sized hunk of clay that broke away. Frantic efforts to save him were to no avail.

On December 26, 2004, a great earthquake shook the floor of the Indian Ocean producing a tsunami that took the lives of almost 230,000 people.

On August 29th, 2005 Hurricane Katrina, one of the most costly and deadly hurricanes in the history of the United States, reached landfall on the Louisiana coast. Almost 2000 people died and an estimated 81.2 billion dollars worth of property damage was done.

Argument

This is an inquiry into a non-religious, or humanist concept of sacred and whether such a concept is meaningful without connection to a religious belief system derived from a higher power. I do not rely much on authorities to develop this argument. I am trying to reach deeply into my personal experience of the world and grapple directly with a concept that is key to our ability to live with one another peacefully. This is my concept of sacred, you are free to accept or reject it. Even so, what I hope to do is to provoke thought and reflection on your part as to what your concept of sacred is and its utility to you.

I am interested in the idea that places, things, or concepts become sacred when respected and actively held up as a standard or apart from abuse and violation. As more of us hold these places, things, or concepts up and apart from abuse and violation, they become more sacred.

I am a humanist. I don’t believe in a higher power of any kind and have difficulty with words commonly claimed by, and associated with, higher power belief systems. As a refugee from the Christian tradition, I am uncomfortable with anything that leads me back to it.

That said, I believe there are many words and attendant concepts that are still powerful when weaned from their supernatural connections and understood as human constructs which help us make our earthly existence tolerable, orderly, even happy.

This post began by reaching back to the beginning of time as we know it, and marching forward through a representative litany of the rumblings of the Universe which, as it turns out, regularly produces moments of great violence. I can find no reason to believe there is judgment involved in this churning of matter and energy in space over time. The universe is indifferent to what you and I perceive as the consequences of this churning. Stuff happens. There is no place or thing you, I, or anyone can wish to set apart from violation that this churning unfolding of the universe cannot easily wipe away. Things come and go according to the physical laws of the universe and that is that.

As my extremely partial list of cosmic calamities shows, we are at the mercy of these eruptions. Eventually, the universe will throw something big at us and there won’t be much we can do beyond trying to be among the survivors.

Very early on humanity noticed that the world could be a brutal place; that they had little control over the calamities that befell them; that, even if they managed to avoid those calamities it was inevitable they would one day feel their vitality slip away until they ceased to be. The unfolding of our lives after a certain point, 30, maybe 40 years of age, can seem a steady and continual chipping away by violations, small and large.

Thinking of it this way, it is not hard to understand why humanity develops a profound longing for a place where the continual indignities of the world don’t reach them; a place eternally free from violation, a sphere of perfection, a Heaven. Or that they might imagine a place that was beyond those violations in the distant past, a Garden of Eden. Or even that they would contemplate a place of eternal punishment with violations of the most awful kinds with which to damn the wicked, a Hell.

This line of thinking helps me understand how elaborate fantasies like Heaven, the Garden of Eden and Hell came into being and how so many of us believe in their literal existence. What one of us wouldn’t love to find a place free of violation or doesn’t dream of eternal punishment for those who do us grievous harm?

A Humanist Definition

I don’t believe these places are anything more than mythological constructs addressing deeply seated existential needs we all have. Once we free the concept of sacred from the supernatural we can start to examine it for its utility to our earthly existence. As we do, we recognize that a critical component of the concept of sacred is our experience of violation. We are more than creatures that live from day to day. We experience ourselves in the world, remember how things were, and dream about how things could be. We invent words like sacred and violate to share our hopes, fears and desires with one another. And, unfortunately, the violations we were most concerned about when we first identified the concept, are those that we all too readily perpetrate on one another. It is no accident that eight of the Ten Commandments are proscriptions against actions that violate and that six of those are proscriptions against actions through which we violate one another. Long ago, we came to the conclusion that a civil society required us to collectively set things apart from our propensity to violate them. We had to agree that certain things were sacred.

Sacred is a human construct. The universe, except through us or any other intelligent creatures there may be, does not make distinctions about what can and can’t be violated. Mother Nature will as easily wipe away a temple as uproot a tree or kill off the dinosaurs. We make the distinctions because they help us navigate our journey through life and our relationships with all the journeys unfolding around us.

There are all kinds of sacred when we define it simply as that which we agree to aspire to or hold apart from violation. Most, if not all of us, have numerous places, objects and aspirations that are sacred to us. We give them special reverence because they have utility in establishing meaning and giving orientation to our lives. They help us know who, what and where we are. We are incredibly distressed when someone takes, destroys, or desecrates them.

Let’s explore the sacred places that are our homes. Have you ever stopped to think how different it is to be on one side or the other of the threshold of the front door of your home; about how the simple act of crossing from one side to the other substantially changes your frame of mind? We cross it many times a day, and each time we do we experience a transition from domestic sanctuary to the bustling and demanding outer world or the reverse. There is a particular feeling to walking out the door to go to work; a particular feeling to walking out the door to run a few errands; a particular feeling to coming home at the end of a long day and closing the door behind us, leaving the energy draining challenges and frustrations of that day outside. There is significance to the invitations we offer to an acquaintance or friend to cross the threshold and join us inside our homes. As visitors, we intuitively understand that crossing the threshold into the home of another is a privilege and with it goes their trust that we will not violate the sanctity of it. What one of us does not cherish the sanctity of our homes? What one of us would not feel violated by the intrusion of the outside world in some uninvited way?

Significantly, we broadly agree that “one’s home is one’s castle,“ and that we are entitled to enjoy it free of violation by others. And, recognizing that there are at least a few for whom this common agreement does not hold, we deploy security tactics to keep ourselves free from violators, and we collectively agree to punish those who violate.

It is not only personal places and things that develop a sacred character. We collectively identify things, places, even concepts as sacred. Most of us commonly acknowledge that churches, synagogues, temples, shrines, etc., and all the relics that fill them, are sacred. We don’t necessarily share the beliefs of the communities to whom these places and things belong. We don’t experience them as sacred in the way those communities do, but we understand and respect that significance and, in so doing, reinforce their sanctity.

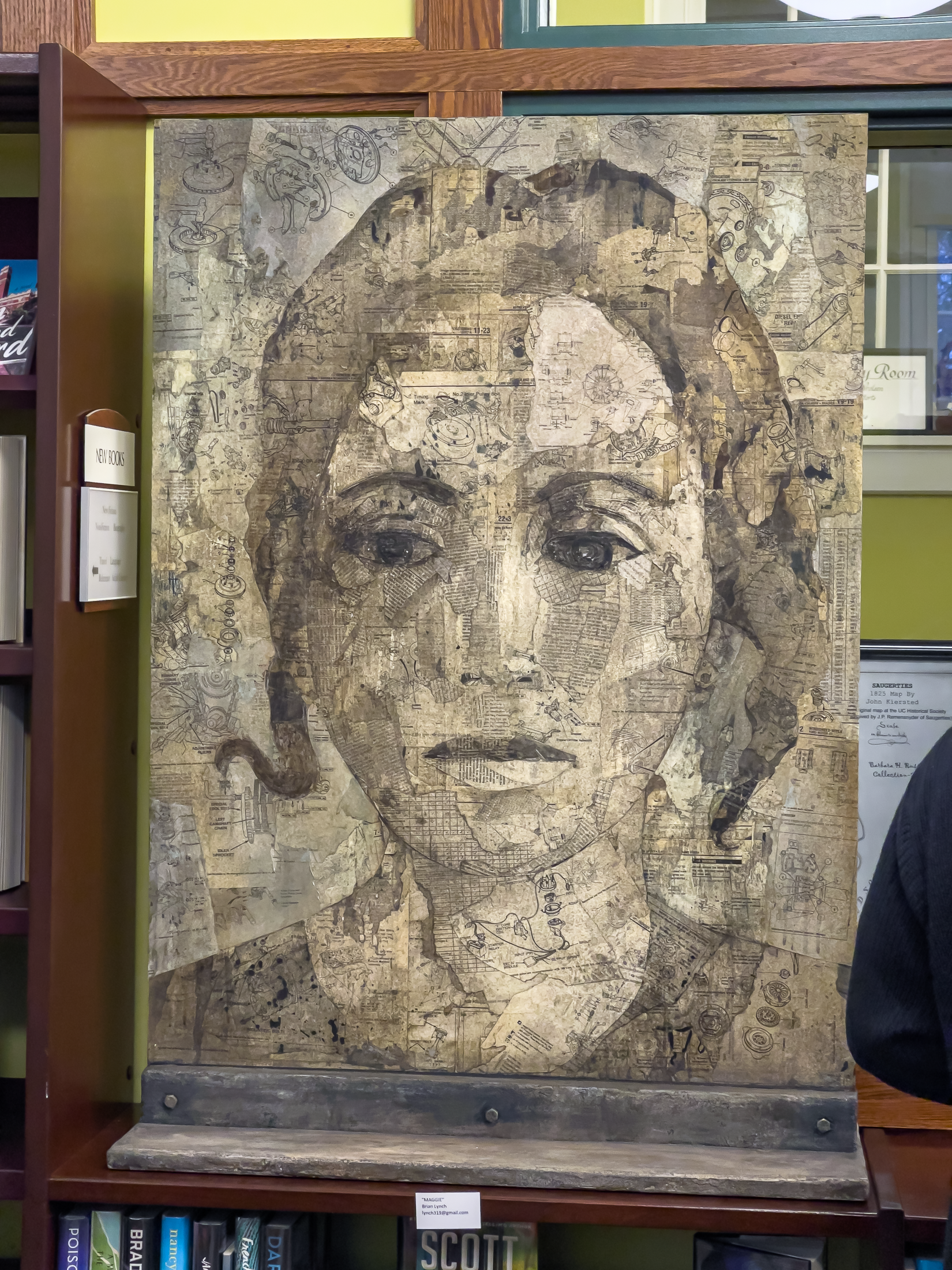

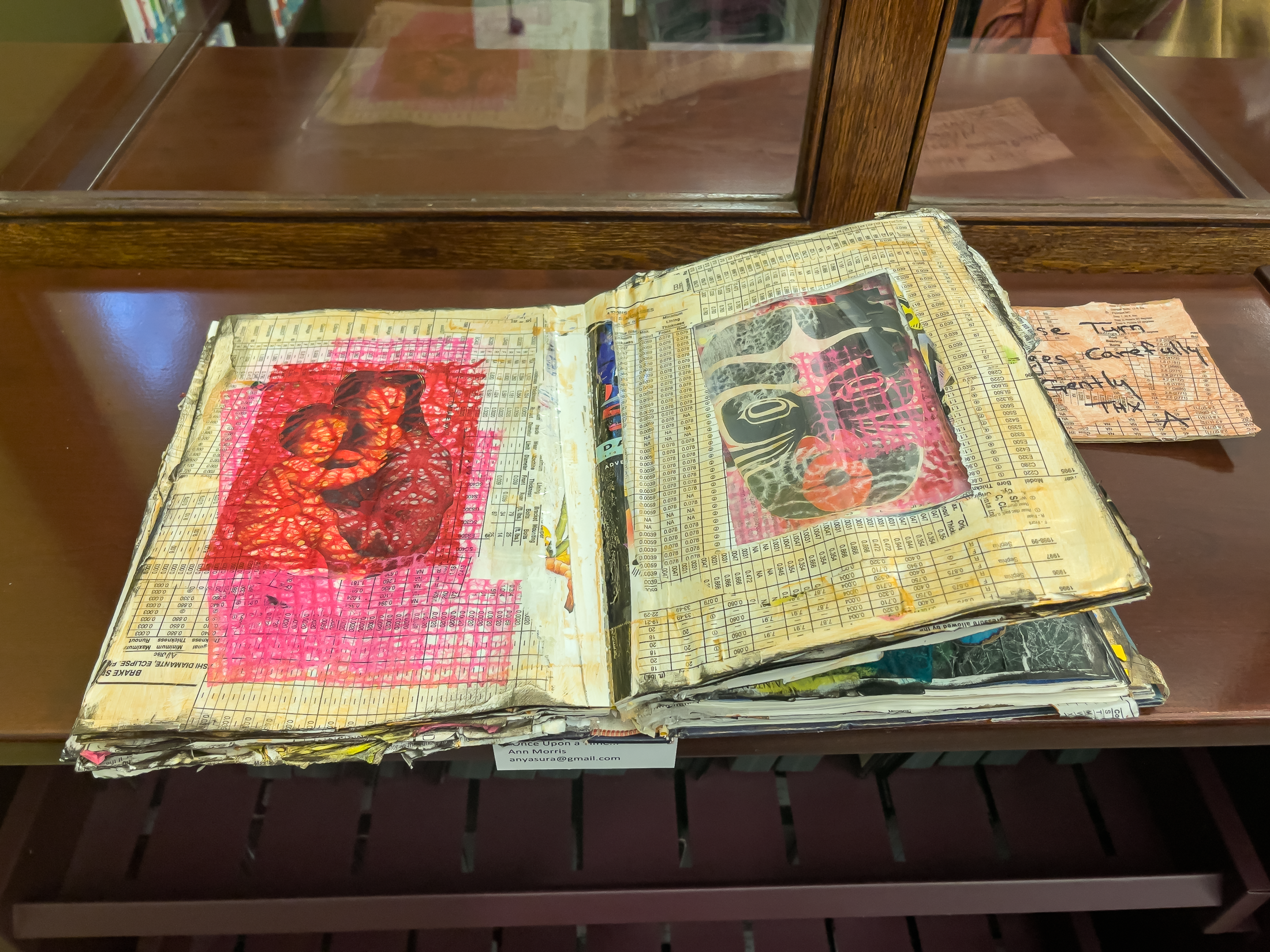

Somewhat less obvious would be the sacredness of our “secular” cultural institutions. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and my current favorite temple of contemplation, the DIA Art Museum in Beacon, NY, are examples of secular cultural places filled with sacred objects. Objects that are profoundly important to our collective memory of who and what we are.

We often hear the complaint “is nothing sacred anymore?” We nod our heads knowingly when we hear it because we have often experienced the violation of something that had relevance to our history and sense of being and therefore a measure of sacredness. Everywhere I look there is evidence of people deciding what is sacred and what is not. A surprising amount of the world is sacred to somebody, and an equally surprising amount of the world is sacred to large numbers of us.

Our ideas about what is sacred and what is not churn continuously. Part of that churning is an often necessary challenge to the status quo. We are, and should be, always asking, is this still worthy of setting apart or upholding?

Understanding the power of the sacred, when a collective of people seeks to dominate another, they will desecrate the places and things sacred to them. You destroy the will of a people by destroying what is sacred to them.

Places and objects are not all that can be sacred. Perhaps some of the most significant, as well as most difficult to parse, are conditions or states of being:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

These rights are sacred and not to be violated. Exactly what is meant by “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” is open to interpretation and there was, and still is, some distance to go before these rights in fact apply to everyone, regardless of religious affiliation, gender, sexual orientation or race.

It is in the realm of such concepts that we find the most significant instances of the sacred. This is the realm in which we are most likely to find agreement that approaches universal on what is deserving of reverent respect.

The sanctity of human life is a concept much of humanity clings to, despite the difficulty we have agreeing on when it begins and when it is acceptable to terminate a nascent one. The listing of calamities at the beginning avoids human created tragedies to make the point that “stuff happens,” without getting caught up in the why and wherefore of human violence. But, let’s admit the obvious, humanity is capable of incredibly destructive and violative acts. We are all too well reminded of this by the events of September 11th, the genocide of Darfur, the daily tragedies that occurred in Iraq and Afghanistan, the unbearable tragedies of mass shootings, the war in Ukraine.

It is our capacity to violate one another and everything living around us that makes a concept of the sacred important.

Usefulness

What, then, is the usefulness of a concept of the sacred without a belief in God? What should we as a society be holding apart from violation?

On the outside of the building of The New York Society for Ethical Culture, a humanist religious community I was a member of for years, this is inscribed:

Dedicated to the ever increasing knowledge, and practice and love of the right.

And above the stage in the auditorium:

The place where people meet to seek the highest is holy ground.

Notice that it is not the building that is holy, but any place where people meet to seek the highest. This building has importance as the first home of Ethical Culture. It has achieved sacred status within the Ethical Culture movement and even to many non-members familiar with the good that has emanated from it. But for Ethical Culture, the highest level of sacred is reserved for something else.

The place where people meet to seek the highest is holy ground. The highest what? Why should we want to know and appreciate and love “the right?” Because the fundamental belief of Ethical Culture, and humanism in general, is in the worth and dignity, indeed, the sanctity of every human being; because every human being brims with potential and has the capacity to do remarkable things; because achieving that potential requires that we conduct ourselves and the affairs of our institutions in such a way that we honor that worth and dignity. We honor that worth and dignity by refraining from unreasonably or selfishly restricting an individual’s potential. And even more importantly, we are enjoined to conduct ourselves in a way that moves us and those around us ever closer to the realization of that remarkable potential.

Humanists do not assume we are helpless to help ourselves. In fact, the assumption is that in the here and now, we are the only ones who can help ourselves. And how do we go about helping ourselves? We do that by building relationships with integrity that honor and respect the worth and dignity of all involved. That is the fundamental core of Humanism.

Relationships with Integrity

How do we build relationships with integrity? I’d like to answer this question by looking at a set of human capacities that are essential to possessed and clearly demonstrate if there are to be relationships with integrity. They are courage, honesty, fairness, forgiveness, tolerance, respect, empathy, and joy. Together, these capacities determine the integrity of our relationships by setting the level of trust and commitment we have to one another.

When an individual has courage, we know they will stand by us under difficult situations and do the right thing by us in those situations. This will be true whether doing right by us means facing an outer peril together or the inner peril of our anger when they tell us something we don’t want but need to hear. We know they will have the capacity to do the right thing, regardless of the consequences for themselves. Several of the other capacities are intimately linked to, even dependent on courage.

When an individual is both honest and has courage, we know we can rely on them to give an accurate account of any given situation and that they will do so regardless of how it reflects on us or them. We know they will have the capacity to admit mistakes.

The capacity to be fair tells us that an individual can regularly overcome prejudices, regardless of what they are or how they arise, and that they can consistently resist the temptation to benefit to another’s detriment.

An individual’s capacity for forgiveness tells us that mistakes can be made, but they will always be reviewed in the light of our intentions and the circumstances. It also tells us there is room for redemption, even when the transgression is significant. Who among us has not transgressed significantly at least a few times in our lives?

The capacity for tolerance tells us that there will be room for our differences, without which a diverse group of individuals cannot hope to congregate in peace.

The capacity for respect tells us that we will have worth and dignity in an individual’s eyes and that they will honor that worth and dignity even while disagreeing with us or having their faith in us challenged.

An individual’s capacity for empathy tells us they are able to understand the world as we see and experience it.

And finally, an individual’s capacity for joy lets us know that they can join together with us in optimism, wonderment and a full appreciation of all that is possible.

Combine these capacities together, add the leavening of the experience of one another over time, and you have the prime content of any relationship with integrity, trust. To come to a place of mutual trust and respect is the mother of all sacred places. It is only from this place that we can help one another to reach his or her greatest potential.

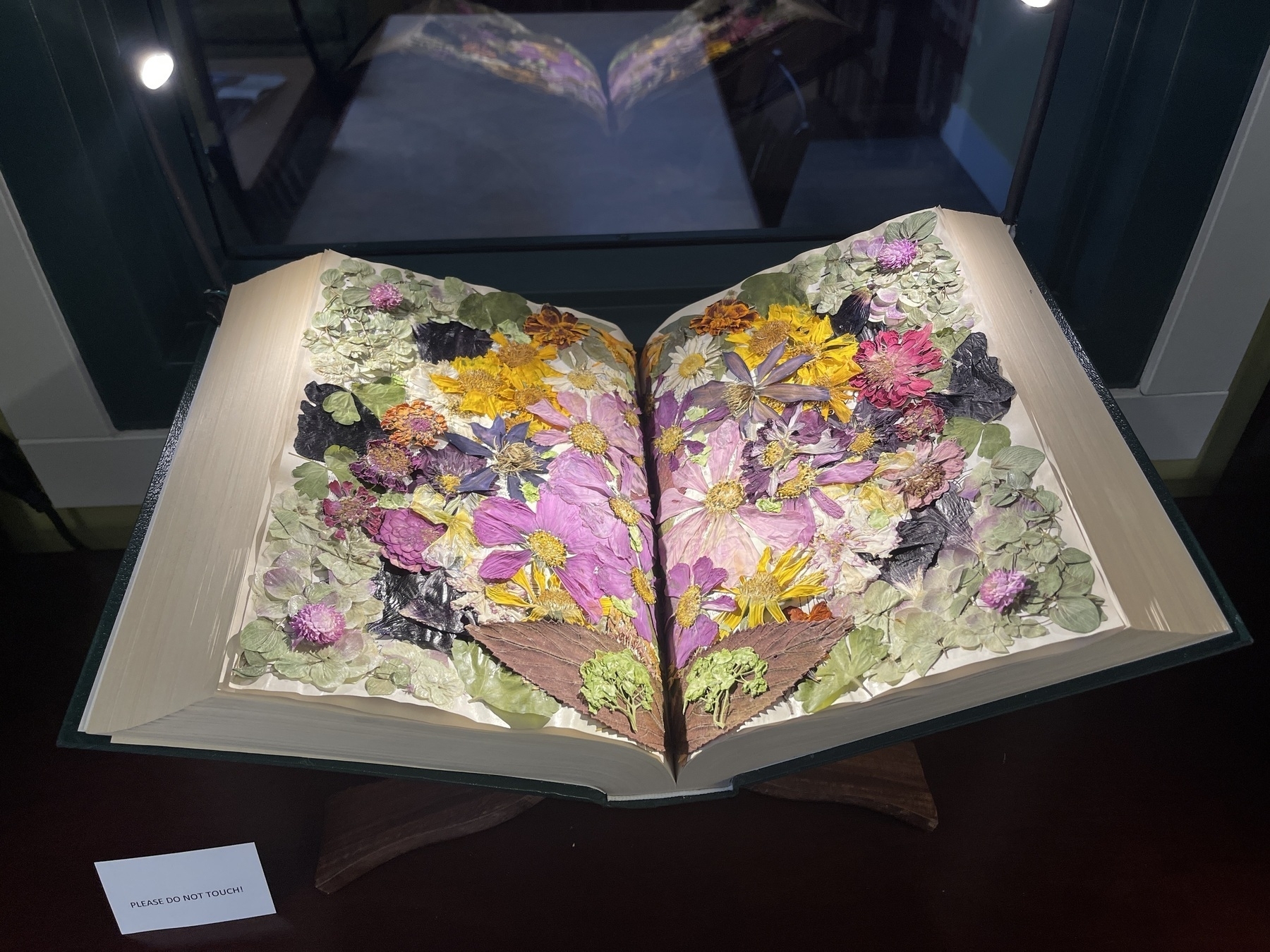

It is not easy work to get to this place. Possessing this set of capacities is not a given. We must work on it throughout our lives. Even if we have all of these capacities in good measure, it takes time and effort for individuals to come together and create that space of mutual trust and respect. And once achieved it is an exquisite, but delicate flowering. Failing, even modestly, in any one of these capacities can damage or shatter it. Even so, it is a place of sanctity that is eminently worth trying for, again, and again, and again.

Sacred is created through an act, or a series of acts of respect and honor. By offering our respect and honor, we acknowledge the importance of right relationship to a place, an object, an individual, a concept, and in doing so, we hold them apart from abuse and violation. This is true whether we do so as individuals or collectively. The significance of the sacred is contained in its power to center us on what is most important to our lives. When we find people, places, things or concepts worthy of honor, and we honor them, they become beacons from which we obtain our bearings. They helps us solidify ourselves and move out with confidence. Only by honoring and protecting these beacons can they be of value to us. For each of us there are numerous individuals, places, things, and concepts which we honor and the fabric of our being, both individual and collective, is woven around them. We define ourselves through what we choose to include and exclude from the realm of the sacred.

When we understand the sacred as being created by an act or a series of acts of respect, then we also understand to what extent the world can become sacred. If we choose to honor and treat with respect everything that impinges on our being, the entire world becomes sacred. If we honor nothing, then the entire world is profane. We must recognize, however, that whatever is not honored and made sacred becomes open to abuse and violation. A world in which nothing is sacred is a world of anarchy.